NOTES ON BARNEY/BRITT/McCARTHY

Meditations on last month's discourse surrounding Vincenzo Barney's Vanity Fair article detailing the illicit relationship between Cormac McCarthy and his "muse," Augusta Britt.

“What, did you expect the man who wrote Blood Meridian to be ‘normal’?” Evidently, many did. Or if they didn’t, at least expected abnormality in a more predictable, ‘digestible’ way. Perhaps it’d have been more palatable if he hit people, had a violent temper. Maybe slapped his wives, smacked his kids. Or “poisoned cats,” and “mugged cub scouts,” as he wrote in his private, revelatory letters. Writing about that level of brutality, with that amount of dexterity, almost presupposes some sort of familiarity, some depth of experience that allows for that presence of mind. But I’ll admit, I wouldn’t have logged Cormac McCarthy as an ephebophile. Though still, maybe ‘ephebophile’ is too strong a label… There is, to my (our) knowledge, no evidence of patterned behavior. Only one singular, transformative, attraction. Cormac McCarthy is guilty of statutory rape. 43 on 17. Debatably the greatest American novelist of the past half-century transgressed one of, if not the most, socially taboo moral frameworks. What does it mean? How are we to evaluate him? And in our evaluating him, how are we to evaluate ourselves?

For much of the past weeks I’ve been fixated on Vincenzo Barney’s scoop article in Vanity Fair about McCarthy’s illicit, lifelong love affair with “five-foot-four Finnish-American badass cowgirl” Augusta Britt. For all of the criticism of Barney’s writing, statements that it’s grandiose, over-the-top, overwritten, etc. etc., it’s stuck with me. It’s memorable. I don’t care for the lede, I think it’s silly, ‘90s-movie trailer cheesy, and find the repeated usage of the second person and literary descriptions… questionable, to say the least. But also, to be honest… I kind of like them, too! ‘Faulkner, Hemingway, YOU!’ It’s bold, memorable! The piece flourishes for its florid prose. How many articles stay with you, days, weeks later? Dominate national, cultural discourse, in this way? Scant few. None recently I can remember. And yet, there’s this notion that Barney is a “bad writer.”1 I think that’s projection. I think he’s a good writer, actually. But more importantly he was, is, a trustable chronicler. Would another reporter have been able to get Britt to break her silence on the story? Maybe. But likely not with such candor. Or comfort. Several (likely jealous) journos have suggested that she deserved her story told differently, by a more credentialed, ‘credible,’ writer. I find that proposition absurd, and patronizing. Ironically, denying Britt her agency while lamenting how it was impeded. She chose Barney in particular to tell it, ahead of all others. She deserves that deference, and he deserves that grace. Journalism is a multifaceted art, it’s not just what’s written on the page, despite our inability to observe beyond it. It’s the work that goes into getting it on the page, the relationship-making, the bridge-building, the schmoozing and positioning, the little things that make a work bigger, better, increase its depth, refine its breadth. It’s difficult to imagine a piece of this scale and substance existing sans his emergence.

But that aside, much of the controversy surrounding Barney relates to his engagement with McCarthy. He’s accused of sidestepping his abuse, and too rarely reckoning with the gravity of his reporting that, yes, McCarthy legally, definitionally, raped a teenager. According to his detractors, Barney contextualizes the circumstances without criticizing those actions — and that, they imply, is tantamount to tolerating his crimes. But what more was he supposed to do? And what would they suggest he do, that wouldn’t imperil the existence of his piece? Or worse, betray the trust of the subject of his piece, who he’d befriended, laughed with, and spent months with? Britt didn’t want a moralizing story or a ‘hit job.’ She’d kept quiet in fear of it. In defending her humanity, was Barney to deny hers?

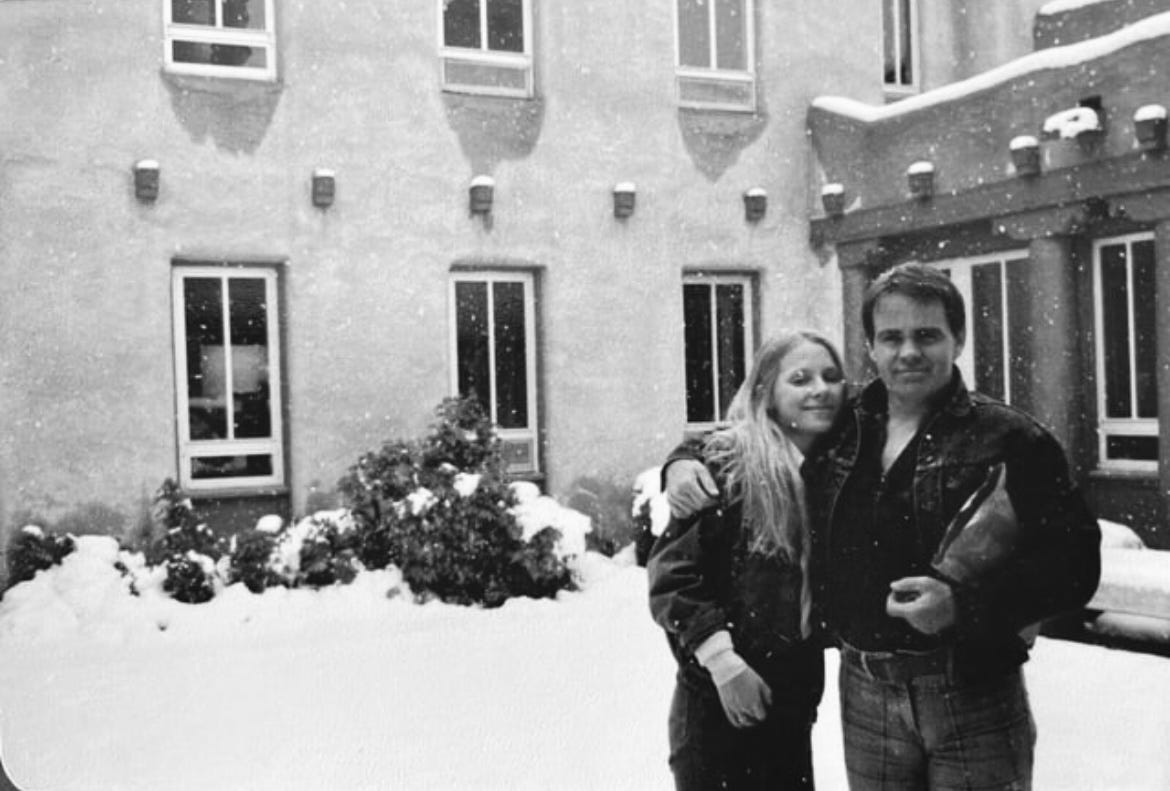

Instead, Barney does the opposite, outsourcing much of the story’s telling to Britt, without extensive editorializing. He questions her on her time with McCarthy, and in their recorded dialogue, Britt talks of how they met, how they exchanged letters back and forth (which, she recounts as later being uncomfortable with), their Southwestern Loli-like liaisons, their runaway to Mexico, their peyote bonding, and his shielding truths from her. She doesn’t avoid his indiscretions, she paints a full picture; it’s only that her idea of those indiscretions differ in nature from those of her white-knighting, if well-meaning, defenders. Britt’s chief issue with McCarthy isn’t his “grooming,” which she laughs off, but his making a muse of her. His using her for inspiration and channeling her life and surroundings into his work. Her primary feelings of violation are not physical, but metaphysical. Which is curious insofar as it relates to Barney’s critics — in ignoring Britt’s sentiments, they’re by proxy imposing their worldviews unto her. She must feel the way they feel, it’s how she’s supposed to feel, she was taken advantage of. They’re flattening her into a tragic character, just as McCarthy grafted her into a romantic one, and conscripting her story in service of a broader cultural conflict.

There’s a charitable read of their intentions here; that an example must be made of McCarthy, that he must be condemned in order to ward off other would-be predators and signal that within the arts, creation is not absolution. The take isn’t without basis; already, implicitly, waves of the usual suspects have rushed to defend yet another great man under assault, in ignorance, or tolerance, of his behavior. It should go without saying, but perhaps can’t, that McCarthy invites personal criticism. But should that criticism go so far, as some have suggested, to prevent his literary canonization?2

There’s a broader trend within the arts and those that consume them to judge everything in black-and-white, all-or-nothing terms. We as people often possess an overpowering tendency to construct indiscriminate moral schema with which to order the world around us. An artist is either good or bad, praiseworthy or condemnatory, the multifaceted nature of their person ignored. But, invariably, inevitably, we also make exceptions for those we hold in affection, be they personal or parasocial. McCarthy is another in a long line of these figures, a genius polymath with a grisly life. The man chose poverty to pursue literary authenticity, even though that poverty harmed his family. Then abandoned that family to run off with a runaway, and abdicated adulthood and responsibility in singular pursuit of sexual obsession. Our subjective feelings do not wipe away artists’ objective harms, and any exoneration based on entertainment value does a disservice to those who’ve suffered in its service. But neither should those feelings, at least completely, characterize the content of his work. His work is lauded as brilliant. He is, without question, brilliant. Does that brilliance dim, even if there’s a darkness to him? Now that we ‘know’ there’s a darkness to him? I’d argue no.

There’s no separating the art from the artist, the author inevitably shapes the work. Especially now, when the artist so plainly dictates access to the work. But a balance must be struck; we should evaluate the totality of their character while appreciating the beauty, or lack thereof, of their craft.

“You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the devil was at his elbow. A creature that can do anything. Make a machine. And a machine to make the machine. And evil that can run itself a thousand years, no need to tend it.”

— Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

Brilliant. You totally get what so many missed. This is her story told the way only a true confidante can tell it.

Beautiful essay.

Such a refreshingly nuanced take. Well said!